Overview

- There is a mismatch between Australia’s household makeup — where most are one or two people — and a housing market dominated by larger dwellings, underscoring the need for policy reform to better align homes with real demand.

- 61% of households are just one or two people — but three- and four-bedroom homes dominate the housing stock.

- Couples without kids and people living alone now make up the majority of households, yet policy and planning still focus on families.

More than 60% of Australian households are made up of just one or two people, yet the bulk of our housing stock is built for families.

New analysis from Cotality shows a stark mismatch between who lives in our homes and the kinds of homes we’re building.

Who really makes up Australia’s households?

When most Australians picture the “Great Australian Dream”, they see a family with kids in a three-or-four bedroom house. But data shows that dream does not match reality.

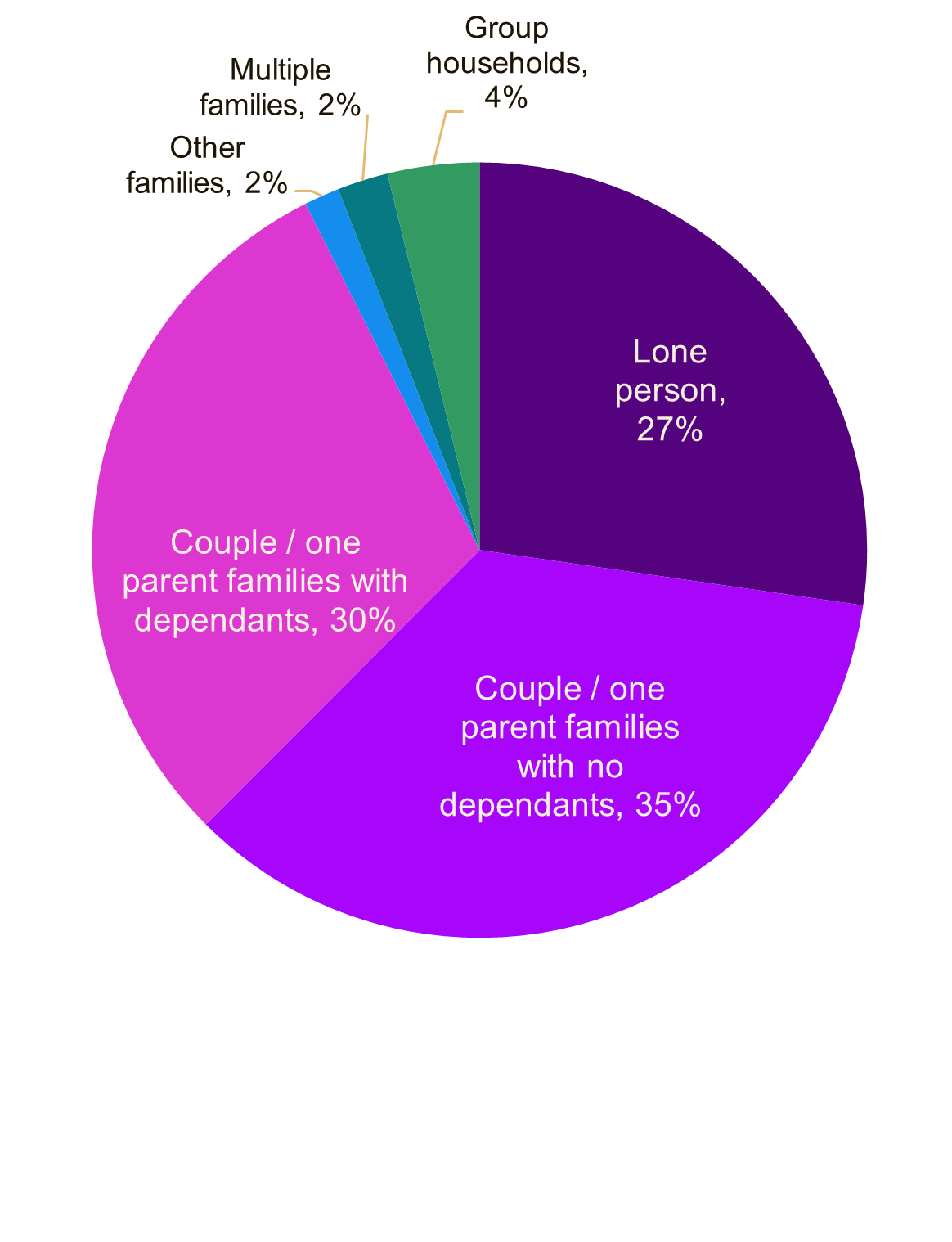

Couples without children and people living alone make up the majority of households, raising questions about how well our housing market is serving real demand. While families are an extremely important consideration for our housing system, demographic data from the ABS reminds us that there are different kinds of households and housing needs.

In fact, only around 30% of Australian households are families with dependants.

A notable 31% are couple families without dependants, and 27% are people living alone.

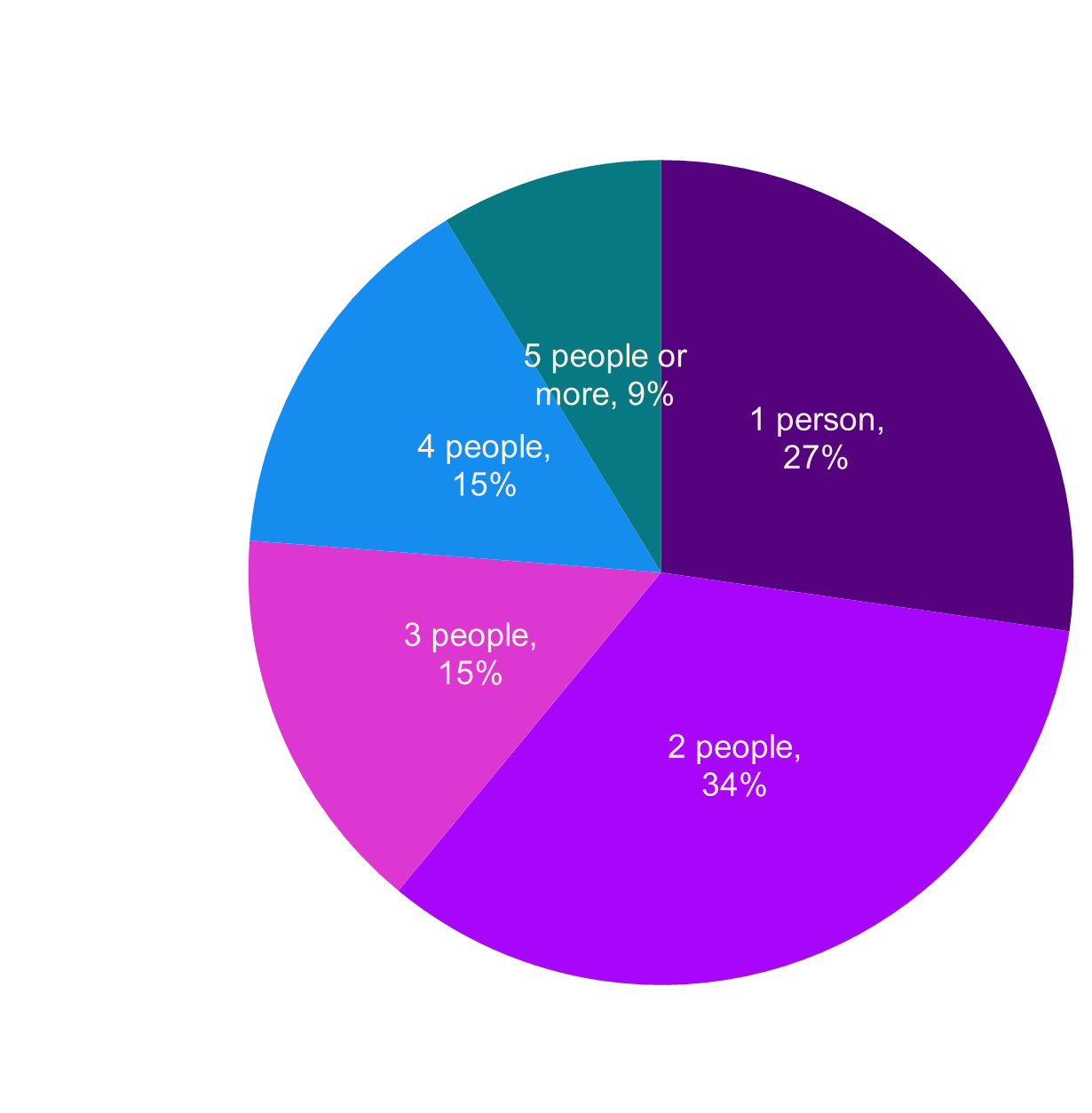

When you look at households purely by number of people, it may be surprising to learn that 61% of Australian households are made up of just one or two people.

Figures 1 and 2 show the make-up of Australian households according to an experimental dataset from the ABS, released as part of the ‘Labour Force Status of Families’ publication.

Of the lone-person households in Australia, the data suggests around 40% are aged 65 and over. Couple households without dependents had an average of 0.8 people aged 65 or over, so it’s reasonable to assume that just under half would be older couples.

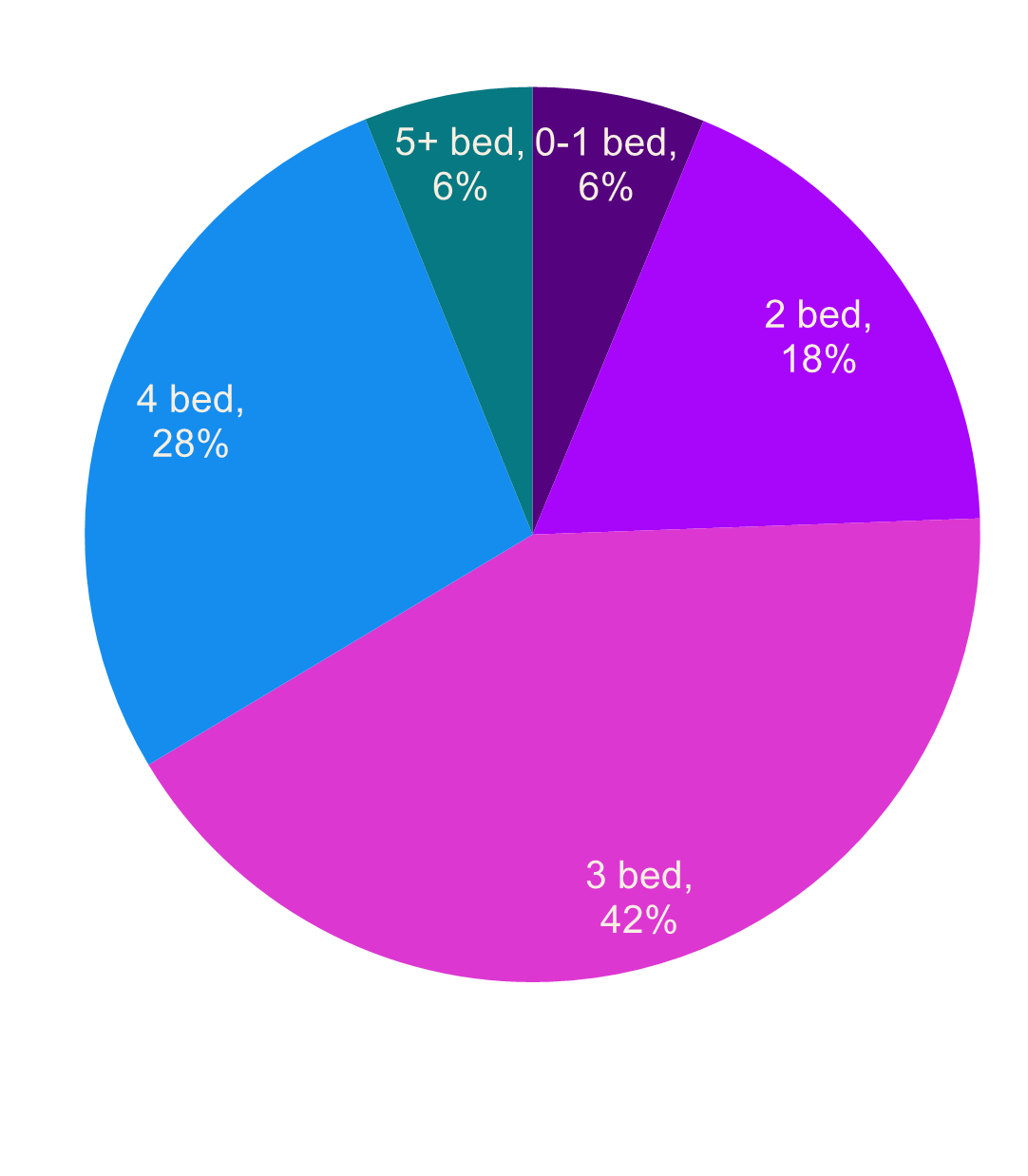

When comparing the number of people in each household (Figure 2) with Cotality data on housing by number of bedrooms (Figure 3), there is a clear mismatch. The highest share of households is two people, but the highest share of housing has three bedrooms. The next-highest share is of one-person households at 27%, but one-bedroom and studio homes together make up just 6% of Australia’s housing stock.

Figure 4 shows a similar situation across the states and territories, with larger housing dominating housing stock, despite most households having just one or two people in them.

Figure 1. Composition of households by type in Australia

Figure2. Households by count of people in Australia

Figure3. Dwellings by bedroom

Why bigger homes still dominate

There is nothing inherently wrong about a dwelling having more bedrooms than people. With the rise of the home office, the desire for in-home care later in life, and space for hobbies and visitors, having additional bedrooms is potentially very attractive. It is also reasonable to assume that many couple family households without dependents have more bedrooms because they are planning to have children.

New houses have also generally become larger over time, with one explanation being that more amenity is needed within the home to account for the growing distance from large commercial centres. As we build further and further out on city fringes, homeowners may find it more convenient to have home amenities like a gym, workspace or home theatre.

However, it is worth noting that of the new housing pipeline overall, the share of units is shifting gradually higher. In the past decade to June 2025, ABS data shows dwellings other than houses made up about 40% of approvals, up from 37% in the decade prior. This may gradually provide more fitting housing options for smaller households.

Cotality data shows there has been high demand for larger dwellings, with the five-year annualised growth rate sitting highest for four-bedroom dwellings nationally (8.7%), compared to just 3.7% for 0-1 bedroom dwellings. In fact, higher capital growth may be part of the reason for trying to buy and hold houses over units, or larger houses over smaller houses.

While there’s nothing wrong with more bedrooms than people in a dwelling, there could be some inefficiencies in the way housing is being allocated. After all, a ‘traditional’ family of four may have more need for a three-bedroom dwelling than a household of two people. Yet at the 2021 census, ABS data showed that for family households, there were more two-person households in three-bedroom dwellings (about 1.3 million), than three or four-person households (about 1.1 million).

The efficiency question

So, what’s the fix?

Governments could make it more expensive to have more housing than you need, and cheaper to live in smaller housing. This leads many to advocate for tax reform like abolishing stamp duty (which makes it cheaper to move housing),and replacing it with a broad-based land tax (which raises costs the more land you own). These options are both politically difficult as it would involve moving from a tax that applies to a small amount of voters each year who purchase property to one that will tax two thirds of voters (property owners).

This would, however, potentially introduce an incentive for older Australians who own their home outright to downsize.

Reforming pension asset tests to include the value of the family home would also help the numbers stack. Strides are already being taken on the supply side to establish well-located apartments in our larger cities, that can accommodate smaller households, but shifting demand through tax reform could help the take-up of these new homes.